Chapter 12 SSE methods

12.1 Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will:

- Understand models that look at the effects of traits on diversification

- Understand some of the problems with these

- Be able to categorize Type I and Type II errors and talk about their relevance.

Make sure to read the relevant papers: https://www.mendeley.com/groups/8111971/phylometh/papers/added/0/tag/sse/

At this point in the course, you should be familiar with working through getting software running. If you want more practice, you could use the vignette written by Jeremy Beaulieu for hisse; running diversitree is similar. However, I think a bigger thing to discuss is how we understand a method is working well, and how we assess whether results are believable. This is especially prominent in discussions of diversification. One great example of this discussion in the literature:

- Nee et al. (1994) “Extinction rates can be estimated from molecular phylogenies”

- Rabosky (2009) “Extinction rates should not be estimated from molecular phylogenies”

- Beaulieu and O’Meara (2015) “Extinction rates can be estimated from moderately sized molecular phylogenies”

- Rabosky (2015) “Challenges in the estimation of extinction from molecular phylogenies: A response to Beaulieu and O’Meara”

And that probably isn’t the last word on this (no, I’m not planning something at the moment). However, despite all the hemming and hawing over what people should do, people still keep using methods: folks using diversitree, BAMM, geiger, or many other approaches merrily estimate extinction rates as a necessary part of their analyses, though they usually don’t focus on them in their studies, instead focusing on diversification (speciation - extinction) or speciation alone. (Note: it is possible to do diversification approaches without estimating extinction rates: one could fix extinction rate at a known value (perhaps using the average duration of fossil “species” to get a fixed estimate), though what is usually done is to fix extinction at 0 (this is called a Yule model, if speciation is constant). This is a bit weird when you think about it: one of the few things we truly know in biology without a doubt is that extinction is far, far from zero in general (though this wasn’t really discovered in Western science until the 19th century)). But as skeptical scientists, we should aim higher. It’s often tempting, especially as students or postdocs facing a difficult job market, to focus on what we can get out: is there an exciting result that can get past peer review and build our fame (maybe, in our tiny circle) and fortune (ha!). But it’s important to take a step back: are we confident enough, truly (not just based on the p-value) that our results are actually discoveries about nature? Diversification is an area (ancestral state estimation is another) where the reality of results is especially worrisome. Take, for example, Etienne et al. (2016), who as part of a broader simulation study, analyzed a dataset of 25 Dendroica warbler species, which is a classic dataset for these studies, fitting a logistic growth model. They found that depending on how the model was conditioned1, something most users would ignore, the estimated carrying capacity (in this model, the number of warbler species at which speciation equals extinction; in other models, this would be the number of species at which speciation is zero, with extinction always set to zero) for warblers is 24.59 or 6.09 or 0.656 species. That means, depending on how one conditions, we should expect the number of Dendroica warblers to stay exactly where it is, crash to around six species, or crash to half a species [and of course, in the latter two cases, stochastic change in number of species will lead to them hitting zero species fairly quickly, which is an absorbing state]. Given the sensitivity of the model to factors like conditioning, any result has to be taken with a great deal of skepticism.

For trait based models, the same history of finding problems and the solutions (or partial solutions) has arisen (there is a paper coming out in the American Journal of Botany in May 2016 that goes into this in more detail). The most relevant parts:

Maddison (2006) (and there were similar points made by others earlier) showed that transition rates and diversification rates can be hard to distinguish. Oversimplifying a bit, but if the rate of going from state 0 to state 1 is higher than the reverse rate, then over time there should be many more taxa in state 1 than 0. If the diversification rate in state 1 is higher than in state 0, there will tend to be more taxa in state 1 than 0. So if you see a tree with more state 1 than 0, is it higher transition rate to 1, or higher diversification in 1? Or is it lower transition to 1 but a high enough diversification rate that it overwhelms it? Or just chance? The paper identified the problem but not the solution: the last line of the abstract is “Studies of biased diversification and biased character change need to be unified by joint models and estimation methods, although how successfully the two processes can be teased apart remains to be seen.”

This was followed up by Maddison et al. (2007) who figured out a method to deal with this: BiSSE. And systematists looked at it, and it was good. There is now a bestiary of similar *SSE models for different kinds of data: QuaSSE, GeoSSE, MuSSE, ClaSSE, and more.

However, there are concerns. The original paper showed that estimating extinction was hard to do accurately, and other papers (Davis et al, 2013) showed that you needed a hundreds of species to find significant results (sorry, Dendroica – you will forever remain a mystery). However, a particular scary paper (and talk at Evolution, where it was presented) was Maddison & FitzJohn (2014). Their paper mostly discussed correlated characters, but has relevance to SSE approaches. If you have a single change on a tree, you don’t know if a higher rate in the clade descended from that branch is due to that trait, some other trait changing on that branch, or some other trait changing on the tree but in a way that makes it mostly on one part of the tree. Rabosky & Goldberg (2015) showed that the way many people interpret BiSSE results, as a testing of a null hypothesis, can be misled if part of the null hypothesis is wrong but not the part you’re interested in. Beaulieu & O’Meara (2016) address some of the Maddison & FitzJohn issues (a character changing elsewhere on the tree driving a result) but not all the issues (a single change being sufficient to give substantial support for an idea that that trait is driving diversification).

12.1.1 Discussion prompts

- What is Type I and Type II error?

- Do we care about them? Why or why not?

- Compare and contrast

- model selection

- null hypothesis rejection

- multimodel inference

- parameter estimation

- What is a good null model for trait diversification?

- What is the model we use?

- How do you know a method is good enough to use?

- in general

- for your data

- Given the controversies about diversification methods, are you willing to use them? Defend your view!

For a lot of these questions, there isn’t a right answer (at least, not one I know, and certainly not an agreement in the field). But it’s worth thinking about as you develop your research career.

Conditional probability is the probability of an event given that some other event has occurred. For example, you could use past information from your department to estimate

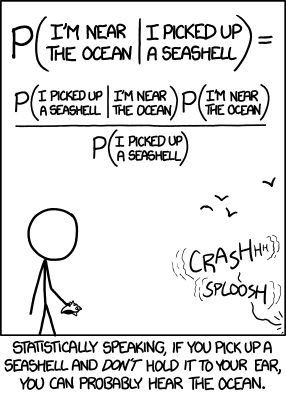

Prob(getting tenure), but it is different if you use information that another event has occurred:Prob(getting tenure | made major discovery in evolution)is different fromProb(getting tenure | four years since last publication). In this domain (diversification alone and diversification plus trait models), we condition on actually having a tree to look at: if the true model is speciation rate equals extinction rate, there’s a good chance that most clades starting X million years ago will have gone extinct, so the ones we see diversified unusually quickly, and this has to be taken into account. The example I usually use for this is the idea that dolphins rescue drowning sailors. It’s known dolphins push interesting objects in the ocean. We could interview previously drowning sailors that dolphins pushed towards shore, and they’ll all say that dolphins saved them, but it’s very hard to interview sailors the dolphins pushed the other way. As always, Randall Munroe’s XKCD explains conditional probability best ↩︎

↩︎