1.9 Weather and trip planning

Whilst it’s good to be able to understand something about meteorology, the most important skill for sea kayakers is being able to interpret a forecast and use it to select a venue and plan a trip. The ability to make good plans comes with time and experience. Hopefully the notes below might help you on your way

1.9.1 Accounting for wind

We need to think about the wind in relation to the coastline that we’re paddling. It might be:

Onshore - we’ll be exposed to the wind and waves, and it may push it towards a hazardous shoreline

Offshore - we may be able to find shelter from the land, but need to be aware of the hazards of being pushed offshore

Along the coastline from in front of us - which is going to make progress hard work

Along the coastline from behind us - which may help our progress, as long as we have the skills to paddle downwind in the forecast wind and wave conditions… and, of course, considered if we need to get back upwind later in the day.

If the wind is strong (say force 4 or more), it often makes sense to seek coastlines that are sheltered from the wind. Be aware that the wind on these coastlines will blow offshore, creating a potential hazard. What seems like a light wind close to land and cliffs may be a strong wind further out. If the group gets blown away from land, getting back to shore may be difficult.

The amount of shelter that the land provides depends on the topography. Flat land without vegetation will provide little shelter. Tall cliffs are likely to provide excellent shelter from the wind - but beware downdrafts in very windy conditions. Any steep coastline, even if cliffs are only a few meters high, can provide useful shelter if a group stays close in under the cliffs. Some coastlines that provide good shelter can have areas where the wind blows strongly off the land. This can occur at gaps in cliff lines and where valleys that run parallel to the wind run down to the sea.

It also makes sense, if planning a round trip, to start by paddling upwind, so that the group gets blown home. This provides a significant safety margin compared to a day that starts downwind.

It’s also worth checking how the wind is blowing in relation to any tidal streams - if the wind is blowing opposite to the tidal stream, rough conditions will often result. There’s more on this effect in the notes on tide and waves.

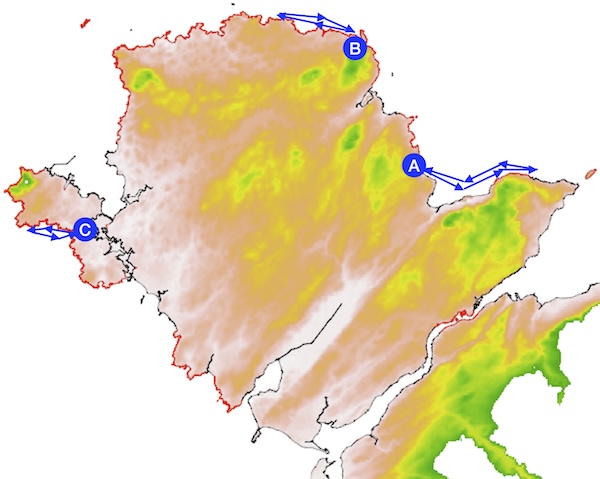

The map below show the island of Anglesey with elevation shown (green areas are ~150m) and cliffs shown as red stretches of coastline.

You are contemplating the paddles shown, all coastal round trips departing and returning to points A, B or C. What is the best option given the following wind forecasts:

Force 1-2 westerly?

Force 3 easterly?

Force 5 south-westerly?

Force 8 south-westerly?

A force 1-2 wind will have less influence on our choice of paddle, so A,B or C will be possible. It may still be good practice to paddle upwind first in case the wind increases (as paddles B and C do), but we might expect paddle A to be well sheltered from this light wind on the east side of the island.

With a force 3 wind, it is sensible to paddle upwind first, then be pushed back to the start by the wind later in the day. Only paddle A starts upwind with an easterly, so this seems the best option.

We’ll likely want to shelter from a force 5 wind. Being on a coast open to the south-west, paddle C will be exposed to the wind. The low-lying valley across the island means that there will likely be little shelter for paddle A. Paddle B makes the most sense. It is sheltered by some higher ground and some sea cliffs. It begins by paddling against any westerly component of the wind blowing along the coast.

In a force 8 wind, shelter is likely to be imperfect on any of Anglesey’s coastlines, given it’s a reasonably low-lying island. The best option is likely to be taking a day off paddling.

1.9.2 Accounting for temperature

Clearly, the risks of hypothermia increase if it’s colder. However, the water temperature may be as big a factor as the air temperature. The water temperature varies little day to day, but does change through the year, being lowest around Januiary to March and highest around August. Dressing for the conditions, and dressing for immersion, can mitigate this risk - but may not be an option for those who don’t yet own dry suits.

Heavy and persistent rain can make a group colder (and more miserable!) if not dressed for the conditions.

1.9.3 Visibility

Fog prevents an obvious challenge if the group’s navigation skills are imperfect - it’s too easy to become disorientated. There’s also a danger of collisions with other craft, especially if you’re paddling in busy areas like harbors or shipping lanes. Be aware that fog is a persistent and somewhat unpredictable occurrence in some parts of the world at certain times of year. For example, between between April and September, warm air passing over the cold North Sea often produces a thick sea fog called the ‘Haar’, which can roll in rapidly to the UKs’s north eastern coastlines with a slight sea breeze.

1.9.4 Thunderstorms

Thunderstorms present dangers to a paddling group that can’t be mitigated by tactics or better skills. Apart from the serious risk of a lightning strike, thunderstorms bring strong wind squalls and reduced visibility. If thunderstorms are forecast, stay off the water. If you get caught out by an approaching storm, find somewhere to land and seek shelter (although not under isolated trees). If there’s no shelter, crouching down away from the water and your boats and equipment is the safest option.

1.9.5 Planning process

The ability to make good plans comes with time and experience. However, the following process might provide a guide for beginners:

A) Choosing where to go

Check wind strength and wave size. Is the wind light enough (e.g. F1) that we can ignore it? Is it strong enough (e.g. F4 or more) that we need to hide from it behind land? If not, it’s probably still sensible to plan a paddle that starts by paddling upwind, so that the wind is behind us at the end of the day.

Assuming we need to consider wind, use an overview map of the area to identify coastlines that we might be able to paddle on and access points that allow us to start upwind. This should give us a short-list of options

Are there any tidal effects (height of tide, tidal streams) to worry about for the areas in our short list? Does this limit options due to (e.g.) wind-against-tide effects, having to paddle against tidal stream or access constraints due to areas drying out?

Are there any other limits to our options or hazards to consider - e.g. other water users, danger areas, logistics, lack of escape routes?

We should now have a list of options that are safe and practical, and need to discuss which we’d prefer to do.

B) Focused planning - once we’ve chosen where to go

Confirm wind, waves and tide for the area. How will they change through the day? How do we expect the shape of the coastline to affect these? Do we need to consider other factors (e.g. shipping, local rules…)?

Where are the put ins and take outs? Where do we park and how far do we need to carry? Where else can we get off if things go wrong?

How far will we paddle? What are the rough timings? Do they fit with weather and tidal changes? Are there critical places that be need to be at specific times? Where will we stop for breaks and lunch?

What are the main hazards and where are the crux points of the trip (e.g. exposed sections, headlands, concentrated wind, waves or tidal stream?). Where are our key decision points to keep going or turn back? How will we make those decisions? Do we have fallback plans if conditions prove worse than expected? At what points do we become committed? What will we do if things go wrong at each point?

Check that the plan is sensible - if not, go back to part (A) and consider other venues.

Finish by copying key information to the map that you will carry on the water. Aim to keep your plans flexible - consider different options and be prepared to change if things don’t turn out as expected.