27 CIs for comparing two independent means

So far, you have learnt to ask a RQ, design a study, classify and summarise the data, and form confidence intervals. In this chapter, you will learn to:

- identify situations where estimating a difference between two means is appropriate.

- construct confidence intervals for the difference between two independent means.

- determine whether the conditions for using the confidence intervals apply in a given situation.

27.1 Introduction: reaction times

Strayer and Johnston (2001) examined the reaction times of students (from the University of Utah) while driving (Agresti and Franklin 2007). In one study, students were randomly allocated to one of two groups: one group using a mobile phone while driving, and one group not using a mobile phone while driving. This is a between-individuals comparison, since different students are in each group. The reaction time for each student was measured in a driving simulator. (The study would be paired if each student's reaction time was measured twice: once using a phone, and once without using a phone.)

Consider this RQ:

For students, what is the difference between the mean reaction time while driving when using a mobile phone and when not using a mobile phone?

The data are shown below.

27.2 Notation

Since two groups are being compared, the two groups are distinguished using subscripts (Table 27.1). For the reaction-time data, we use the subscript \(P\) for the phone-users group, and \(C\) for the control (non-phone users) group.

Using this notation, the difference between population means (the parameter) is \(\mu_P - \mu_C\). Since the population mean are unknown, this parameter is estimated using the statistic \(\bar{x}_P - \bar{x}_C\). The differences could be computed in the opposite direction (\(\bar{x}_C - \bar{x}_P\)). However, computing differences as the reaction time for phone users, minus the reaction time for non-phone users (controls) probably makes more sense: the differences then refer to the increase in the average reaction times when students are using phones.

Be clear about how differences are defined! The differences could be computed as:

- the reaction time for phone users, minus the reaction time for non-phone users; this measures how much faster the reaction times is for non-phone users, on average; or

- the reaction time for non-phone users, minus the reaction time for phone users; this measures much faster the reaction times is for phone users, on average.

Either is fine, provided you are consistent, and clear about how the difference are computed. The meaning of any conclusions will be the same.

| Group \(P\) | Group \(C\) | (\(P - C\)) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population means: | \(\mu_P\) | \(\mu_C\) | \(\mu_P - \mu_C\) |

| Sample means: | \(\bar{x}_P\) | \(\bar{x}_C\) | \(\bar{x}_P - \bar{x}_C\) |

| Standard deviations: | \(s_P\) | \(s_C\) | |

| Sample sizes: | \(n_P\) | \(n_C\) | |

| Standard errors: | \(\displaystyle\text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_P) = \frac{s_P}{\sqrt{n_P}}\) | \(\displaystyle\text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_C) = \frac{s_C}{\sqrt{n_C}}\) | \(\displaystyle\text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_P - \bar{x}_C)\) |

Table 27.1 does not include a standard deviation or a sample size for the difference between means. These make no sense in this context: no set of data exists for which a standard deviation or sample size can be found. For example, Group \(P\) has \(32\) individuals, and Group \(C\) has \(32\) individuals, but the sample size for the difference is not \(32 - 32 = 0\); there are just two samples of given sizes. However, the standard error of the difference between the means does make sense, as the value of \(\bar{x}_P - \bar{x}_C\) varies across all possible samples.

27.3 Summarising data

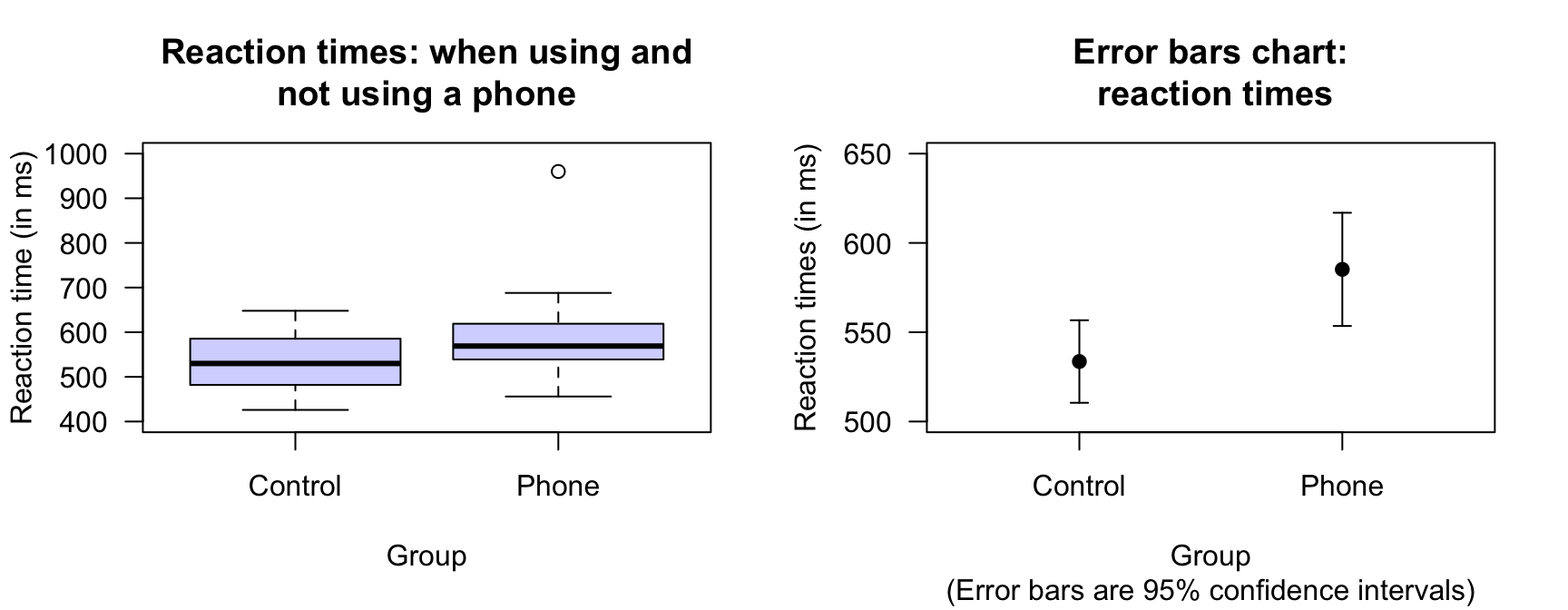

A suitable graphical summary of the data is a boxplot (Fig. 27.1, left panel), which shows that the sample medians are slightly different, and the IQRs slightly smaller, for the phone-using group. One large outlier is present for the phone-using group.

FIGURE 27.1: Left: boxplot of the two groups in the reaction-time data. Right: error bar chart comparing the mean reaction time for students not using a mobile phone (control), and using a mobile phone. The vertical scale is different for the two graphs.

The numerical summary of the data should summarise both groups (i.e., the first two rows of Table 27.2) The differences between the means is crucial (i.e., the third row), since the RQ is about this difference. The information can be found using software (Fig. 27.2).

FIGURE 27.2: Software output for the phone reaction time data

| Mean | Sample size | Standard dev | Standard error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not using phone | \(533.59\) | \(32\) | \(65.36\) | \(11.554\) |

| Using phone | \(585.19\) | \(32\) | \(89.65\) | \(15.847\) |

| Difference | \(\phantom{0}51.59\) | \(19.612\) |

27.4 Error bar charts

A useful way to compare the means of two (or more) groups is to display the CIs for the means of both groups in an error bar chart. Error bars charts display the expected variation in the sample means from sample to sample, while boxplots display the variation in the individual observations. For the reaction time data, the error bar chart (Fig. 27.1, right panel) shows the \(95\)% CI for each group; the mean has been added as a dot.

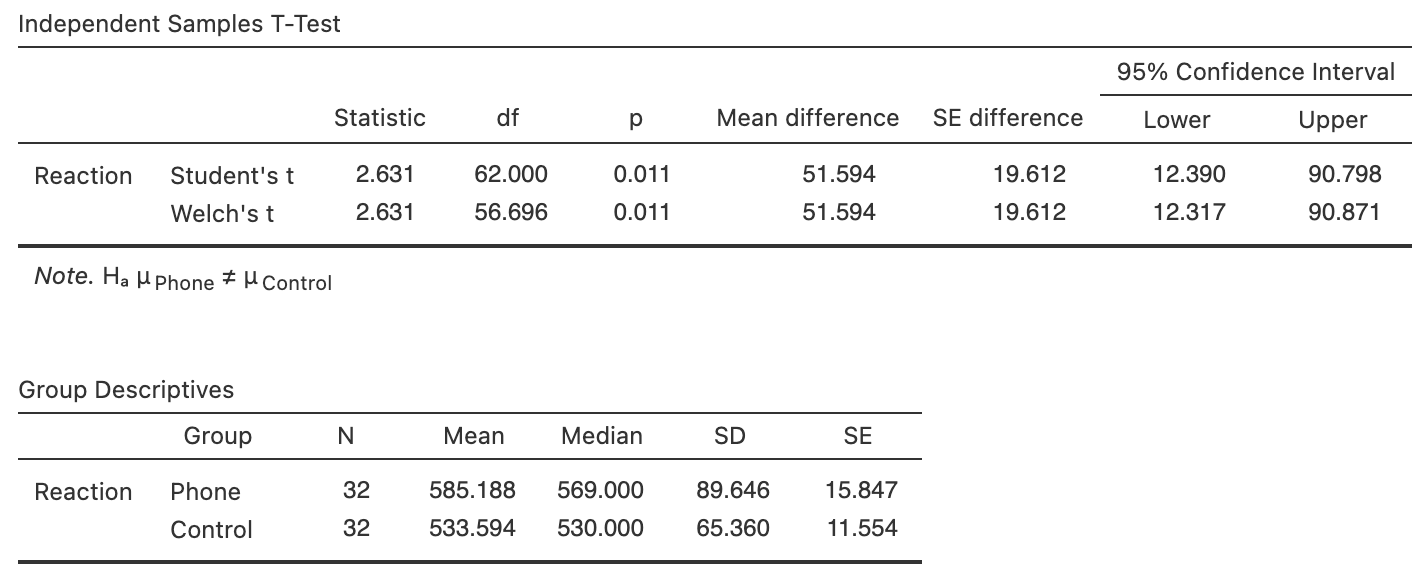

Example 27.1 (Error bar charts) A study (Schepaschenko et al. 2017a) examined the foliage biomass of small-leaved lime trees from three sources: coppices; natural; planted.

Three graphical summaries are shown in Fig. 27.3: a boxplot (showing the variation in individual trees; left), an error bar chart (showing the variation in the sample means; centre) on the same vertical scale as the boxplot, and the same error bar chart using a more appropriate scale for the error-bar plot (right).

FIGURE 27.3: Boxplot (left) and error bar charts (centre. Right) comparing the mean foliage biomass for small-leaved lime trees from three sources (C: Coppice; N: Natural; P: Planted). The centre panel shows an error-bar chart using the same vertical scale as the boxplot. The right error-bar chart uses a more appropriate scale on the vertical axis. The solid dots in the boxplot show the mean of the distributions

27.5 Confidence intervals for \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\)

Each sample of students will comprise different students, giving different reaction times. The sample means for each group will differ from sample to sample, and the difference between the sample means will be different for each sample. The difference between the sample means varies from sample to sample, and so has a sampling distribution and standard error.

Definition 27.1 (Sampling distribution for the difference between two sample means) The sampling distribution of the difference between two sample means \(\bar{x}_A\) and \(\bar{x}_B\) is (when the appropriate conditions are met; Sect. 27.6) described by:

- an approximate normal distribution,

- centred around a sampling mean whose value is \({\mu_{A}} - {\mu_{B}}\), the difference between the population means,

- with a standard deviation, called the standard error of the difference between the means, of \(\displaystyle\text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_A - \bar{x}_B)\).

The standard error for the difference between the means is found using \[ \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_A - \bar{x}_B) = \sqrt{ \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_A)^2 + \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_B)^2}, \] though this value will often be given (e.g., on computer output).

For the reaction-time data, the differences between the sample means will have:

- an approximate normal distribution,

- centred around the sampling mean whose value is \(\mu_P - \mu_C\),

- with a standard deviation, called the standard error of the difference, of \(\text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_P - \bar{x}_C) = 19.612\).

The standard error of the difference between the means was computed using \[ \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_A - \bar{x}_B) = \sqrt{ \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_A)^2 + \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_B)^2} = \sqrt{ 11.554^2 + 15.847^2 } = 19.612, \] as in the software output (Fig. 27.2).

The sampling distribution describes how the values of \(\bar{x}_P - \bar{x}_C\) vary from sample to sample. Then, finding a \(95\)% CI for the difference between the mean reaction times is similar to the process used in Chap. 24, since the sampling distribution has an approximate normal distribution: \[ \text{statistic} \pm (\text{multiplier} \times\text{s.e.}(\text{statistic})). \] When the statistic is \(\bar{x}_P - \bar{x}_C\), the approximate \(95\)% CI is \[ (\bar{x}_P - \bar{x}_C) \pm (2 \times \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_P - \bar{x}_C)). \] So, in this case, the approximate \(95\)% CI is \[ 51.594 \pm (2 \times 19.612), \] or \(51.59\pm 19.61\) after rounding appropriately. We write:

The difference between reactions times is \(51.59\) ms, slower for those using a phone (mean: \(585.19\) ms; s.e.: \(15.85\); \(n = 32\)) compared to those not using a phone (mean: \(533.59\) ms; s.e.: \(11.55\); \(n = 32\)), with an approximate \(95\)% CI for the difference between mean reaction times from \(12.37\) to \(90.82\) ms.

The plausible values for the difference between the two population means are between \(12.37\) to \(90.82\) milliseconds (slower for those using a phone).

Giving the CI alone is insufficient; the direction in which the differences were calculated must be given, so readers know which group had the higher mean.

Output from software often shows two CIs (Fig. 27.2).

We will use the results from Welch's test (the second row), as this row of output is more general, and makes fewer assumptions.

Specifically, the information in the first row (Student's t) is appropriate when the population standard deviations in the two groups are the same; the second row (Welch's t) is appropriate when the population standard deviations in the two groups are not the same.

The information in the second row assumes less, and is more widely applicable.

Most software gives two confidence intervals. We will use the second row of information (the 'Welch's \(t\)' row) because it is more general and makes fewer assumptions. (The information in both rows are often similar anyway.)

From the output, the \(95\)% CI is from \(12.32\) to \(90.87\) ms. The approximate CI and the exact (from software) CIs are only slightly different, as the samples sizes are not too small. (Recall: the \(t\)-multiplier of \(2\) is an approximation, based on the \(68\)--\(95\)--\(99.7\) rule).

27.6 Statistical validity conditions

As usual, these results apply under certain conditions. Statistical validity can be assessed using these criteria:

- When both samples have \(n > 25\), the test is statistically valid provided neither distribution is highly skewed.

- When one or both groups have \(25\) or fewer observations, the test is statistically valid only if the populations corresponding to both comparison groups have an approximate normal distribution.

The sample size of \(25\) is a rough figure; some books give other values (such as \(30\)). The histograms of the samples could be used to determine if normality of the populations seems reasonable. Data with severe skewness or large outliers may need larger sample sizes for the CI to be statistically valid.

The units of analysis are also assumed to be independent (e.g., from a simple random sample).

If the statistical validity conditions are not met, resampling methods may be used (Efron and Hastie 2021).

Example 27.2 (Statistical validity) For the reaction-time data, both samples are larger than \(25\), so the CI is statistically valid.

27.7 Example: speed signage

To reduce vehicle speeds on freeway exit ramps, Ma et al. (2019) studied adding additional signage. At one site (Ningxuan Freeway), speeds were recorded for \(38\) vehicles before the extra signage was added, and then for \(41\) different vehicles after the extra signage was added.

The researchers are hoping that the addition of extra signage will reduce the mean speed of the vehicles. The RQ is:

At this freeway exit, how much is the mean vehicle speed reduced after extra signage is added?

The data are not paired: different vehicles are measured before (\(B\)) and after (\(A\)) the extra signage is added. The data can be summarised (Table 27.3) using the software output (Fig. 27.4). Define \(\mu\) at the mean speed (in km.h\(-1\)) on the exit ramp, and the parameter as \(\mu_B - \mu_A\), the reduction in the mean speed.

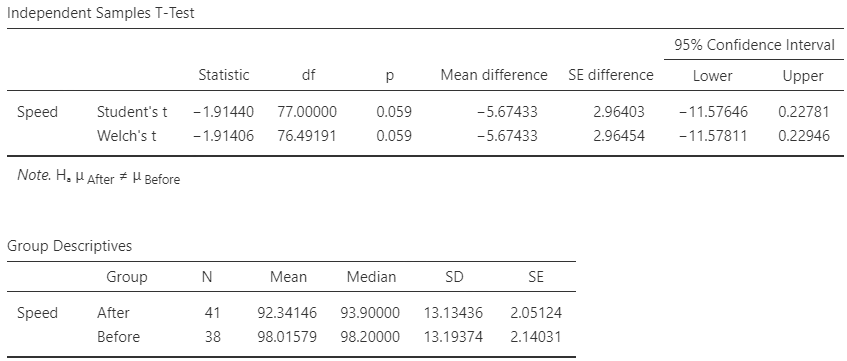

FIGURE 27.4: Software output for the speed data

| Mean | Median | Standard deviation | Standard error | Sample size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | \(98.02\) | \(98.2\) | \(13.19\) | \(\phantom{0}2.1\) | \(38\) |

| After | \(92.34\) | \(93.9\) | \(13.13\) | \(\phantom{0}2.1\) | \(41\) |

| Speed reduction | \(\phantom{0}5.68\) |

The standard error of the difference is \[ \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_A - \bar{x}_B) = \sqrt{ \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_A)^2 + \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_B)^2 } = \sqrt{ 2.05124^2 + 2.14031^2 } = 2.96454, \] and in the second row of the first table in Fig. 27.4.

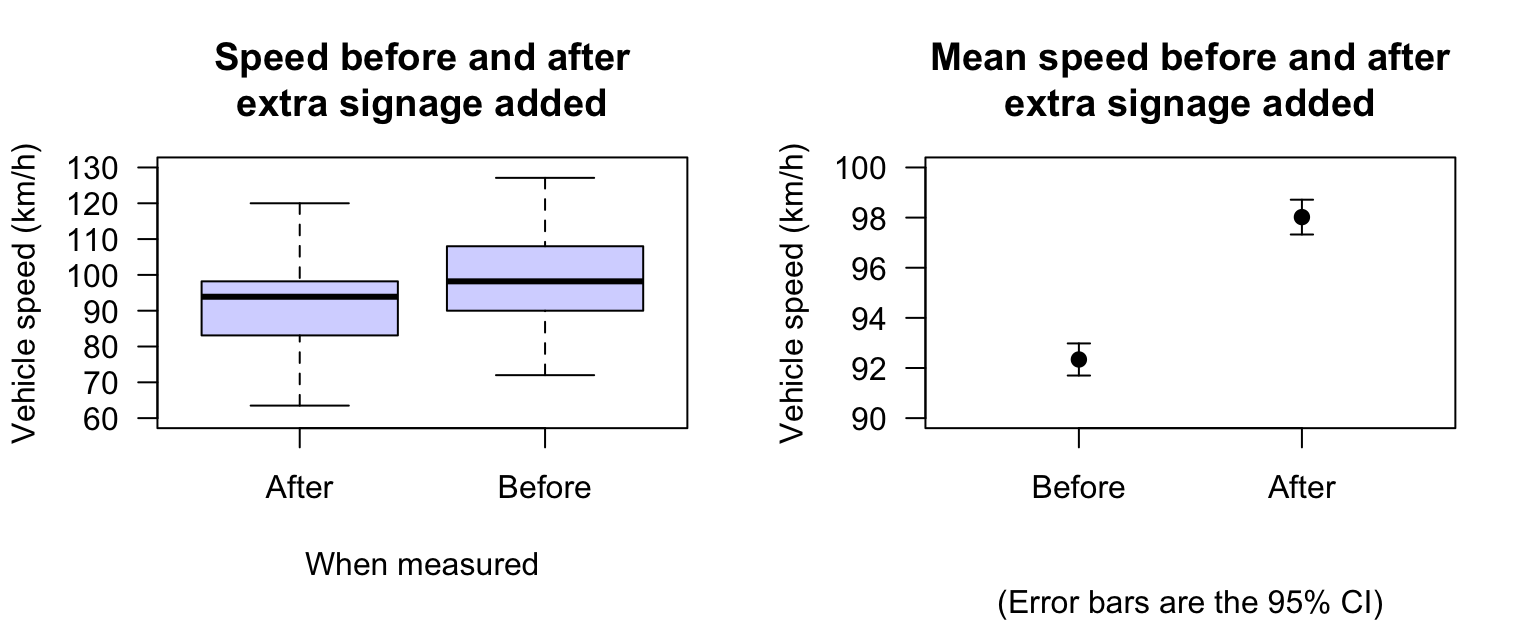

A useful graphical summary of the data is a boxplot (Fig. 27.5, left panel); likewise, an error bar chart can be produced to compare the means (Fig. 27.5, right panel).

FIGURE 27.5: Boxplot (left) and error bar chart (right) showing the mean speed before and after the addition of extra signage, and the \(95\)% CIs. The vertical scales on the two graphs are different.

Based on the sample, an approximate \(95\)% CI for the difference in mean speeds is \(5.68 \pm (2 \times 2.964)\), or from \(-0.24\) to \(11.6\) km.h\(-1\), higher before the addition of extra signage. (The negative value refers to a negative reduction; that is, an increase in speed of \(0.24\) km.h\(-1\).)

From Fig. 27.4, a \(95\)% CI is from \(-11.6\) to \(0.23\) km.h\(-1\), lower before the addition of extra signage (since the After information is given first in the second table of Fig. 27.4). This is equivalent to a \(95\)% CI from \(-0.23\) to \(11.6\) km.h\(-1\), higher before the addition of extra signage. The exact and approximate \(95\)% CIs are almost exactly the same.

The CI means that, if many samples of size \(38\) and \(41\) were found, and the difference between the mean speeds were found, about \(95\)% of the CIs would contain the population difference (\(\mu_A - \mu_A\)). Loosely speaking, there is a \(95\)% chance that our CI straddles the difference in the population means (\(\mu_B - \mu_A\)).

We could write:

The reduction in the mean speed after adding signage is \(5.68\) km.h\(-1\) (before mean: \(98.02\); s.e.: \(2.140\); \(n = 38\); after mean: \(92.34\); s.e.: \(2.051\); \(n = 41\)), with a \(95\)% CI between \(-0.24\) km.h\(-1\) (i.e., an increase of \(0.23\) km.h\(-1\)) and \(11.6\) km.h\(-1\) (two independent samples).

Using the validity conditions, the CI is statistically valid.

Remember: clearly state which mean is larger.

27.8 Example: chamomile tea

(This study was seen in Sect. 26.7.) Rafraf, Zemestani, and Asghari-Jafarabadi (2015) studied patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). They randomly allocated \(32\) patients into a control group (who drank hot water), and \(32\) to receive chamomile tea (Rafraf, Zemestani, and Asghari-Jafarabadi (2015)).

The total glucose (TG) was measured for each individual, in both groups, before the intervention and after eight weeks on the intervention. The data are not available, so a graphical summary of the data cannot be produced. However, a data summary is given in the article (motivating Table 26.3).

The following relational RQ can be asked:

For patients with T2DM, what is the mean difference between the average reductions in TG, comparing those drinking chamomile tea and those who drink hot water?

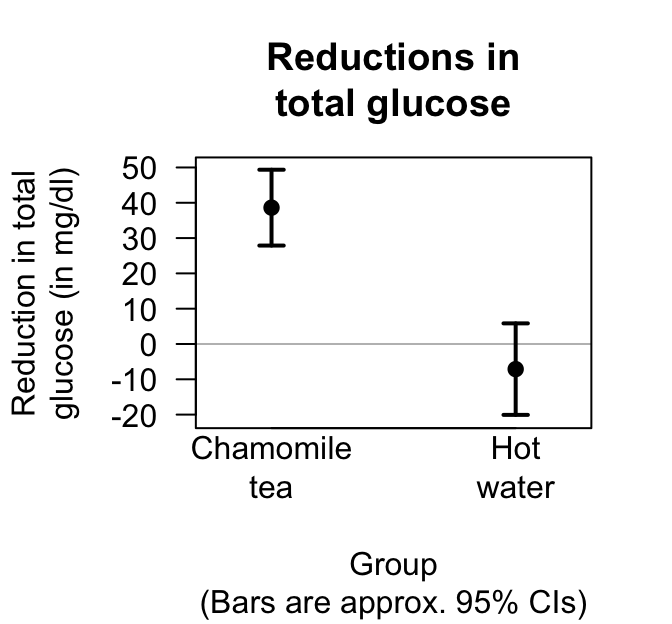

Here, two separate groups are being compared: the tea-drinking group (\(T\)), and the control water-drinking group (\(W\)). Defining \(\mu\) as the mean reduction in TG, the differences between the TG reductions in the two groups is \(\mu_T - \mu_W\). (Of course, the difference can be defined either way, provided we are consistent.) In Sect. 26.7, the mean reduction in each group was estimated. From Table 26.3, the estimate of the mean difference is \(\bar{x}_T - \bar{x}_W = 45.74\) mg.dl\(-1\). The standard error can be determined from the information in the first two rows of the data summary table: \(\text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_T - \bar{x}_W) = 8.42\). Hence, an approximate \(95\)% CI for the difference between the mean reduction is \[ 45.74 \pm (2\times 8.42), \] or from \(28.90\) to \(62.58\) mg.dl\(-1\), with a larger reduction for the tea group. This is a CI for the difference between the mean reductions in each group. The approximate \(95\)% CIs for each group can also be computed, and an error bar chart produced (Fig. 27.6).

FIGURE 27.6: The reduction in total glucose for the chamomile-tea drinking group, and the control group. The horizontal grey line represented no mean reductiion in TG in each group.

We write:

The mean difference between the average reductions in TG is \(45.74\) mg.dl\(-1\), greater for the tea-drinking group, with the approx. \(95\)% CI from \(28.64\) to \(62.84\) mg.dl\(-1\).

This interval has a \(95\)% chance of straddling the difference between the mean reductions in TG. The sample sizes are larger than \(25\), so the results are statistically valid.

27.9 Chapter summary

To compute a confidence interval (CI) for the difference between two means, compute the difference between the two sample mean, \(\bar{x}_A - \bar{x}_B\), and identify the sample sizes \(n_A\) and \(n_B\). Then compute the standard error, which quantifies how much the value of \(\bar{x}_A - \bar{x}_B\) varies across all possible samples: \[ \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_A - \bar{x}_B) = \sqrt{ \text{s.e}(\bar{x}_A) + \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_B)}, \] where \(\text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_A)\) and \(\text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_B)\) are the standard errors of Groups \(A\) and \(B\). The margin of error is (Multiplier\(\times\)standard error), where the multiplier is \(2\) for an approximate \(95\)% CI (using the \(68\)--\(95\)--\(99.7\) rule). Then the CI is: \[ (\bar{x}_A - \bar{x}_B) \pm \left( \text{Multiplier}\times\text{standard error} \right). \] The statistical validity conditions should also be checked.

27.10 Quick review questions

- What is an appropriate graph for displaying quantitative data for two separate groups?

- True or false: The difference in population means could be denoted by \(\mu_A - \mu_B\).

- True or false: The standard error of the difference between the sample means is denoted by \(\text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_A) - \text{s.e.}(\bar{x}_B)\).

- True or false: An error bar chart displays the variation in the data.

27.11 Exercises

Answers to odd-numbered exercises are available in App. E.

Exercise 27.1 Agbayani, Fortune, and Trites (2020) measured (among other things) the length of gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) at birth. How much longer are male gray whales than females, on average, in the population? Summary data are given in Table 27.4.

| Mean | Standard deviation | Sample size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | \(4.60\) | \(0.305\) | \(30\) |

| Male | \(4.66\) | \(0.379\) | \(26\) |

- Define the difference of interest.

- Sketch an error-bar chart.

- Compute the standard error of the difference.

- Compile a numerical summary table.

- Write down the parameter, and its estimate.

- Compute the approximate \(95\)% CI, and write a conclusion.

- Is the CI statistically valid?

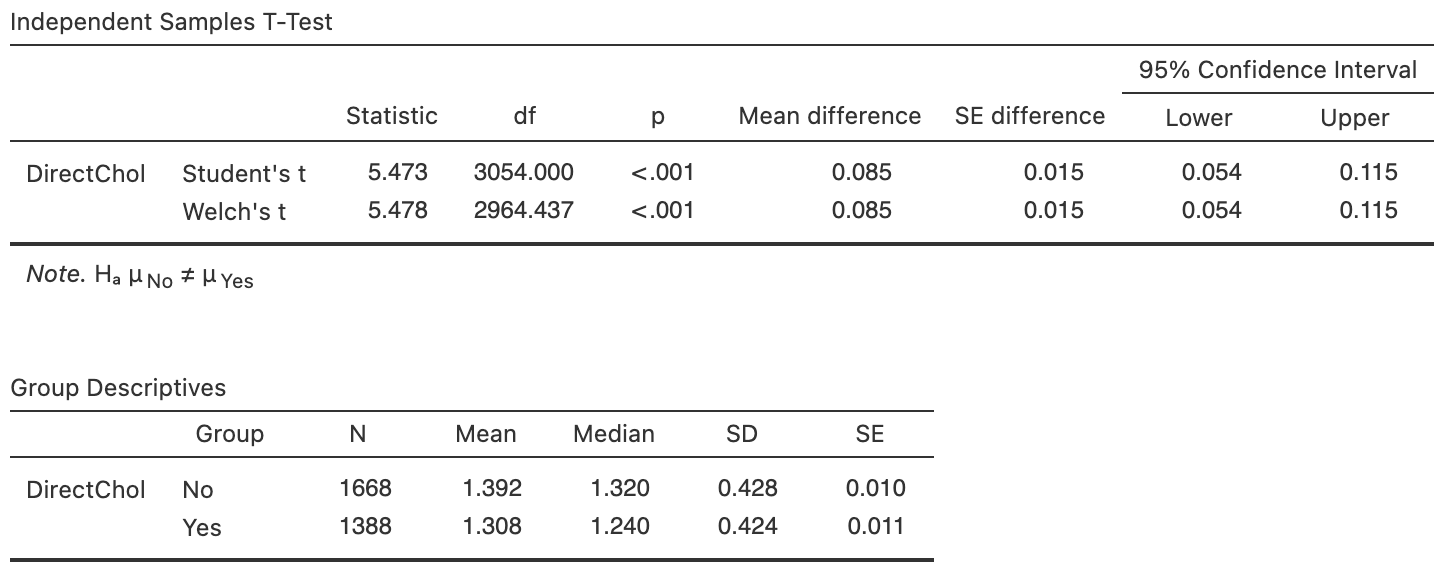

Exercise 27.2 [Dataset: NHANES]

The NHANES study records data annually about a representative sample of Americans.

The data can be used to answer the RQ:

Among Americans, is the mean direct HDL cholesterol different for current smokers and non-smokers?

Use the software output (Fig. 27.7) to answer these questions.

- Define the difference of interest.

- Sketch an error-bar chart.

- Write down the parameter, and its estimate.

- Compute the approximate \(95\)% CI, and write a conclusion.

- Is the CI statistically valid?

FIGURE 27.7: Software output for the NHANES data

Exercise 27.3 Barrett et al. (2010) studied the effectiveness of echinacea to treat the common cold. They compared, among other things, the duration of the cold for participants treated with echinacea or a placebo. Participants were blinded to the treatment, and allocated to the groups randomly. A summary of the data is given in Table 27.5.

- Compute the standard error for the mean duration of symptoms for each group.

- Compute the standard error for the difference between the means.

- Sketch an error-bar chart.

- Compute an approximate \(95\)% CI for the difference between the mean durations for the two groups.

- In which direction is the difference computed? What does it mean when the difference is calculated in this way?

- Compute an approximate \(95\)% CI for the population mean duration of symptoms for those treated with echinacea.

- Are the CIs statistically valid?

- Is the difference of practical importance?

| Mean | Standard deviation | Standard error | Sample size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | \(6.87\) | \(3.62\) | \(176\) | |

| Echinacea | \(6.34\) | \(3.31\) | \(183\) | |

| Difference | \(0.53\) |

Exercise 27.4 Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is pain experienced in the wrists. Schmid et al. (2012) compared two different treatments: night splinting, or gliding exercises.

Participants were randomly allocated to one of the two groups. Pain intensity (measured using a quantitative visual analog scale; larger values mean greater pain) were recorded after one week of treatment. The data are summarised in Table 27.6.

- Compute the standard error for the mean pain intensity for each group.

- Compute the standard error for the difference between the mean of the two groups.

- In which direction is the difference computed? What does it mean when the difference is calculated in this way?

- Compute an approximate \(95\)% CI for the difference in the mean pain intensity for the treatments.

- Compute an approximate \(95\)% CI for the population mean pain intensity for those treated with splinting.

- Are the CIs statistically valid?

| Mean | Standard deviation | Standard error | Sample size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise | \(0.8\) | \(1.4\) | \(10\) | |

| Splinting | \(1.1\) | \(1.1\) | \(10\) | |

| Difference | \(0.3\) |

Exercise 27.5 [Dataset: Dental]

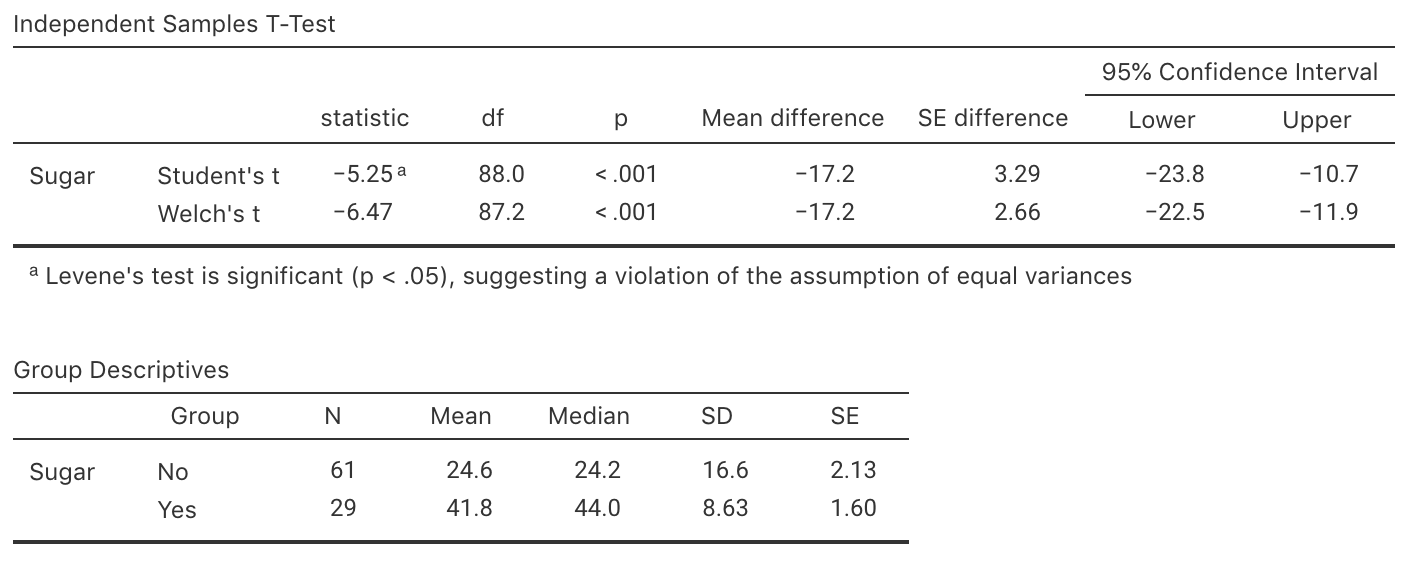

Woodward and Walker (1994) examined the sugar consumption in industrialised countries (mean: \(41.8\) kg/person/year) and non-industrialised countries (mean: \(24.6\) kg/person/year)

Using the software output (Fig. 27.8), write down and interpret the CI.

FIGURE 27.8: Software output for the sugar-consumption data

Exercise 27.6 [Dataset: Deceleration]

To reduce vehicle speeds on freeway exit ramps, Ma et al. (2019) studied using additional signage.

At one site (Ningxuan Freeway), the deceleration of vehicles was recorded at various points on the freeway exit for \(38\) vehicles before the extra signage was added, and then for \(41\) vehicles after the extra signage was added

(Exercise 15.10)

as the vehicle left the \(120\) km.h\(-1\) speed zone and approached the \(80\) km.h\(-1\) speed zone.

Use the data, and the summary in Table 15.7, to address this RQ:

At this freeway exit, what is the difference between the mean vehicle deceleration, comparing the times before the extra signage is added and after extra signage is added?

In this context, the researchers are hoping that the extra signage might cause cars to slow down faster (i.e., greater deceleration, on average, after adding the extra signage).

- Identify clearly the parameter of interest to understand how much the deceleration increased after adding the extra signage.

- Compute and interpret the CI for this parameter.

Exercise 27.7 [Dataset: ForwardFall]

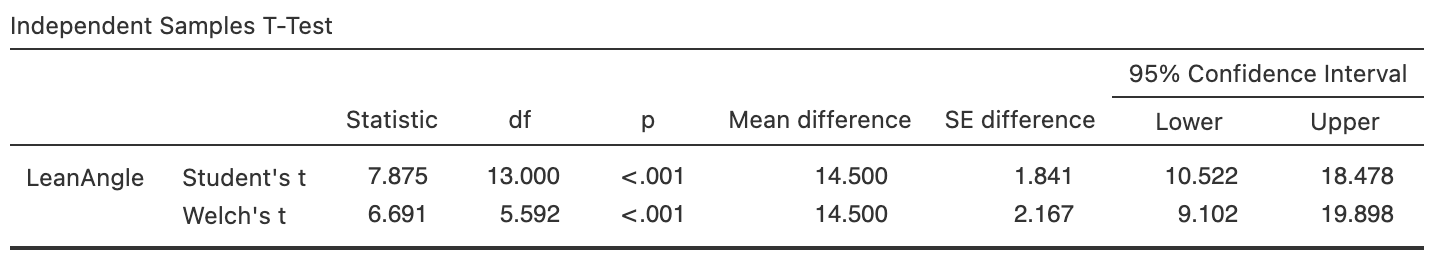

Wojcik et al. (1999) compared the lean-forward angle in younger and older women.

An elaborate set-up was constructed to measure this angle, using a harnesses.

Consider the RQ:

Among healthy women, what is difference between the mean lean-forward angle for younger women compared to older women?

The data are shown in Table 15.6.

- What is the parameter? Describe what this means.

- What is an appropriate graph to display the data?

- Construct an appropriate numerical summary from the software output (Fig. 27.9).

- Construct approximate and exact \(95\)% CIs. Explain any differences.

- Is the CI expected to be statistically valid?

- Write a conclusion.

FIGURE 27.9: Software output for the lean-forward angles data

Exercise 27.8 Becker, Stuifbergen, and Sands (1991) compared the access to health promotion (HP) services for people with and without a disability in southwestern of the USA. 'Access' was measured using the quantitative Barriers to Health Promoting Activities for Disabled Persons (BHADP) scale. Higher scores mean greater barriers to health promotion services. The RQ is:

What is the difference between the mean BHADP scores, for people with and without a disability, in southwestern USA?

- Define the difference. Write down the parameter, and its estimate.

- Sketch an error-bar chart.

- Compute the standard error of the difference.

- Compile a numerical summary table.

- Compute the approximate \(95\)% CI, and write a conclusion.

- Is the CI statistically valid?

| Sample mean | Standard deviation | Sample size | Standard error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disability | \(31.83\) | \(7.73\) | \(132\) | \(0.67280\) |

| No disability | \(25.07\) | \(4.80\) | \(137\) | \(0.41010\) |

| Difference | \(\phantom{0}6.76\) | \(0.78794\) |

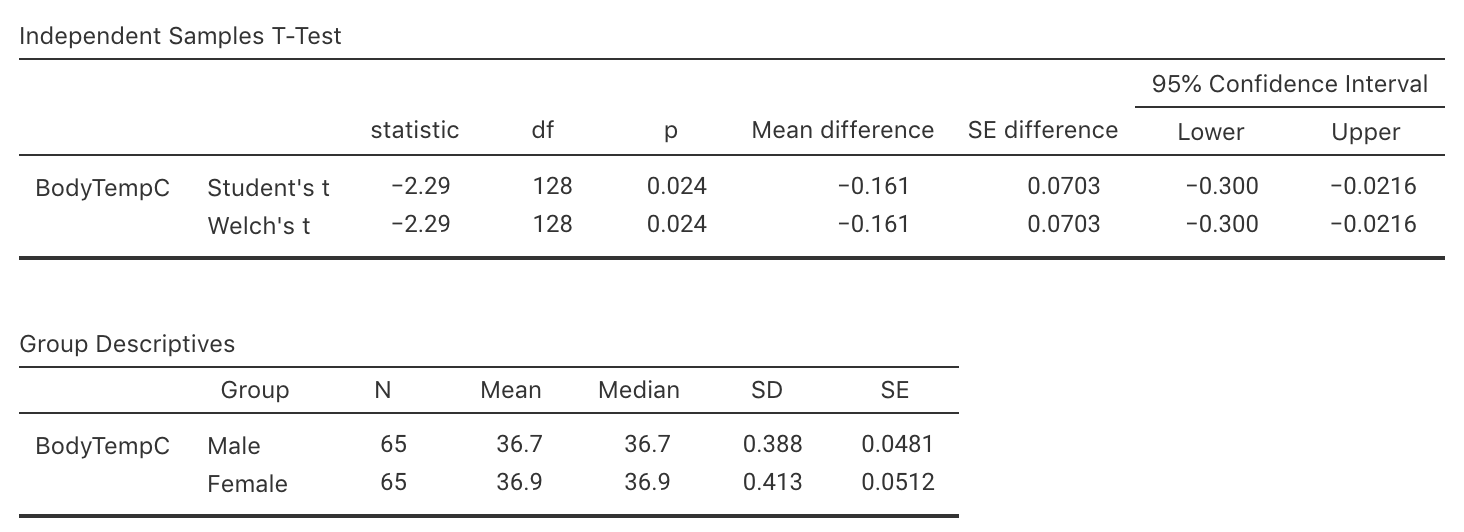

Exercise 27.9 [Dataset: BodyTemp]

Consider again the body temperature data from Sect. 31.1.

The researchers also recorded the gender of the patients, to compare the mean internal body temperatures for males and females.

Use the software output in Fig. 27.10 to construct an approximate \(95\)% CI appropriate for answering the RQ.

FIGURE 27.10: Software output for the body-temperature data

Exercise 27.10 D. Chapman et al. (2007) compared 'conventional' male paramedics in Western Australia with male special-operations paramedics. Some information comparing their physical profiles is shown in Table 27.8.

- Compute the missing standard errors.

- Compute an approximate \(95\)% CI for the difference in the mean grip strength for the two groups of paramedics.

- Compute an approximate \(95\)% CI for the difference between the number of push-ups for the two groups of paramedics.

- Discuss the conditions required for statistical validity.

| Conventional | Special Operations | |

|---|---|---|

| Grip strength (in kg) | ||

| Mean | \(51\) | \(56\) |

| Standard deviation | \(\phantom{0}8\) | \(\phantom{0}9\) |

| Standard error | ||

| Push-ups (per minutes) | ||

| Mean | \(36\) | \(47\) |

| Standard deviation | \(10\) | \(11\) |

| Standard error | ||

Exercise 27.11 [Dataset: Anorexia]

Young girls (\(n = 29\)) with anorexia received cognitive behavioural treatment (Hand et al. (1996)), while another \(n = 26\) young girls received a control treatment (the 'standard' treatment).

All girls had their weight recorded before and after treatment.

s1. Determine the gain in each individuals girls weight. 1. Compute a CI for the mean weight gain for the girls in each group. 1. Compute a CI for the mean difference between the weight gains for the two treatment groups.

Exercise 27.12 Researchers studied the impact of a gluten-free diet on dental cavities (Khalaf et al. 2020). Some of the summary information regarding the number decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT) is shown below.

| Diet | Sample size | Mean | Standard deviation | Standard error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeliac | 23 | 8.39 | 4.4 | 0.92 |

| Non-coeliac | 23 | 8.17 | 4.1 | 0.86 |

| Difference | 0.22 | 1.3 |

An exact \(95\)% CI is given as for the difference is \(-2.32\) to \(2.76\).

Using the \(68\)--\(95\)--\(99.7\) rule gives a slightly different CI. Why?

True or false: the difference is computed as the number of DMFT for coeliacs minus non-coeliacs.

True or false: one of the values for the CI is a negative value, which must be an error (as a negative number of DMFT is impossible).

-

We are \(95\)% confidence that the difference between the population means is:

- Smaller for coeliacs;

- Between 2.32 higher for non-coeliacs to 2.76 higher for coeliacs.

- Between 2.76 higher for non-coeliacs to 2.32 higher for coeliacs.